Optimizing High-Throughput SEM for Large-area Defect Characterization in AM Steel

Methodology

Experimental Methods¶

Samples were manufactured using Fe7336 powder on a S235JR baseplate via Powder Plasma Arc Additive Manufacturing at the Technical University of Munich. A single track of 10 cm in length was manufactured using Argon as shielding gas. The welding torch was operated at 120 A and 20 V, with a travel speed of 0.002 m/s and a standoff distance of 10 mm. A sample was cut from the central area of the weld track, ground and polished to 1 µm diamond size, and finished with OPS polishing.

SEM imaging was carried out using a ThermoFisherScientific Helios 5 Hydra PFIB system equipped with MAPS software (for acquisition and stitching of subsequentially taken SEM images, i.e. tiles), utilizing an interpolated focus strategy. Since the SE signal is primarily sensitive to surface structure (topology), it was chosen for surface defect analysis, using the Everhart-Thornley detector (ETD). The accelerating voltage was set to 30 kV with a beam current of 6.4 nA, and the working distance was maintained at 4.2 mm. To improve the image stitching quality, tile overlap was set to 10 % in both X and Y directions, with an image resolution of 1536 × 1024 pixels per tile. SE image acquisition settings were varied by adjusting the dwell time (0.1 µs, 0.3 µs, 0.5 µs, 0.75 µs, 1 µs, 5 µs, and 10 µs) and pixel size (48.8 nm, 97.6 nm, 195.3 nm, and 390.6 nm per pixel). Due to MAPS software restrictions, only full tiles could be acquired, meaning that not all datasets represented the exact same area. To standardize the comparison, we used the alignment tool within the MAPS software to crop a consistent area of 1.1 × 1.5 mm from all datasets.

Although the SEM acquisition software provides estimated acquisition times, these values were not suitable for direct comparison since they correspond to differing areas. Instead, we scaled the estimated times according to the cropped area and calculated a relative time factor based on the benchmark dataset used in this study (10 µs dwell time and 195.3 nm pixel size), which was defined as 100%. Table 2.1 compares the parameters investigated and their relative acquisition times in percentages.

Table 2.1:MAPS software estimated acquisition times are presented as relative percentages, benchmarked against the reference dataset (10 µs and 195.3 nm, set at 100%)

| Pixel Size [nm] | Dwell time [µs] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 5 | 10 | |||

| 390.6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 14 | ||

| 195.3 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 33 | 100 | ||

| 97.6 | 33 | 37 | 41 | 47 | 52 | 135 | --- | ||

| 48.8 | 134 | 151 | 167 | 188 | 209 | --- | --- | ||

Defect Detection based on local contrast conditions¶

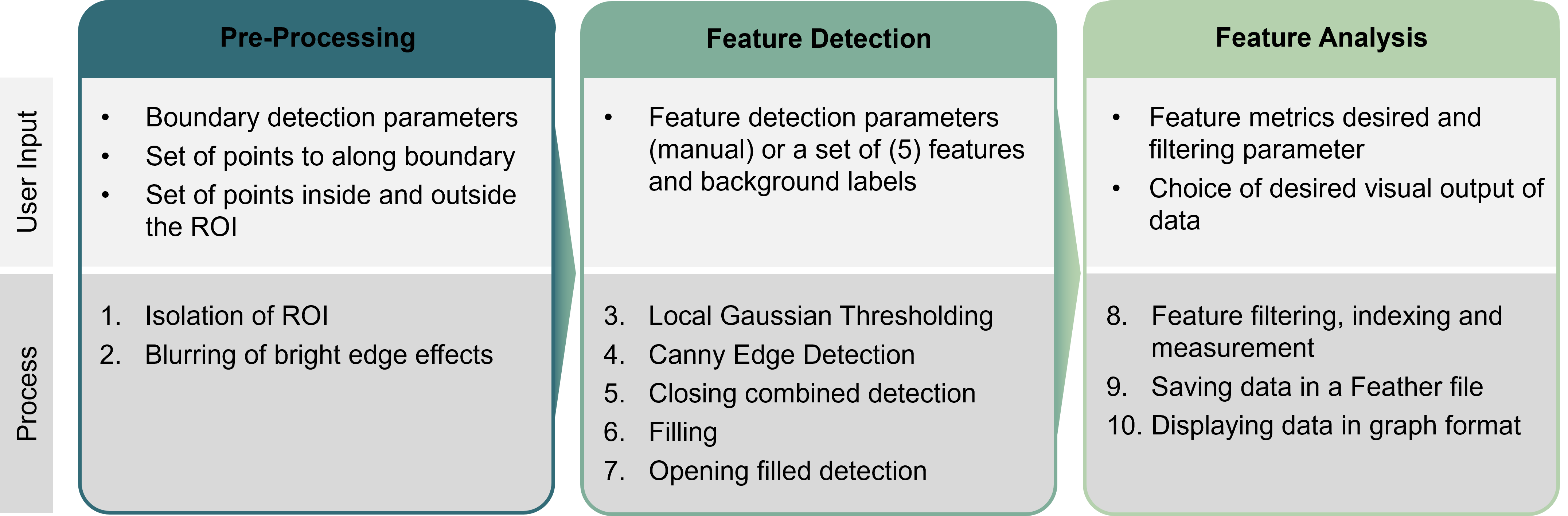

Tiles were stitched into micrographs using MAPS, with blending between tiles as well as tile-to-tile contrast normalization. We developed our own python-based algorithm for automatic detection of defects in micrographs, ensuring consistent accuracy even with variations in contrast and brightness across large-area scans.

Figure 2.1 highlights the general overview of the workflow. For a more detailed description of the individual steps and interactive tools we refer to the section Algorithm details

Figure 2.1:Illustrated Workflow in Defect Detection Algorithm with highlighted inputs.

All steps in the workflow are designed to be adaptable, allowing modifications to accommodate specific imaging conditions. Given the varying SEM image acquisition parameters, Gaussian and Canny thresholds require adjustment Bradski, 2000. To achieve optimal settings, Bayesian optimization is applied to fine-tune these parameters for each dataset. The results presented in this study reflect parameters determined through this approach.

Additionally, to further address varying SE imaging conditions, a denoising strategy for SEM images is explored using a deep convolutional neural network (HR-SEM denoising approach), as demonstrated by Lobato et al., 2024.

Algorithm details¶

In this section, we provide a detailed breakdown of the workflow illustrated in Figure 2.1, emphasizing our algorithm’s flexibility to handle diverse image conditions—such as brightness, contrast and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) in our micrographs. All scripts needed to implement this workflow are available on GitHub for individual use. Additionally, we developed a manual labeling tool that enables comparison of the algorithm’s results with subjective assessments, enabling a direct evaluation of the algorithm’s accuracy against human identification.

Pre-Processing - Identification of region of Interest¶

SEM micrographs are loaded in supported formats (.tif for standard images and .raw for large areas) and processed to subtract their background, isolating the region of interest (ROI). For AM steel samples, this includes separating the fusion boundary from the baseplate material. BSE images can be used for this step due to their strong contrast, due to differences in chemical composition and crystal orientation. The ROI, defined by the fusion boundary, is identified using Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm, adapted from Cormen et al., 2009. This method relies on user-defined points, with a minimum of a start and end point, and calculates the shortest gradient-based path. By adapting to local intensity gradients, the algorithm accurately traces the ROI boundary, ensuring robustness even in areas with varying contrast levels. Alternatively, the ROI can also be determined by the user defining an area on the sample.

To mitigate the impact of bright edge artifacts in SE images Reimer, 1998, selective blurring is applied to high-intensity regions with pixel values exceeding 200 (after normalizing brightness values from 0 to 255), effectively reducing noise amplification in surrounding areas.

Feature Identification¶

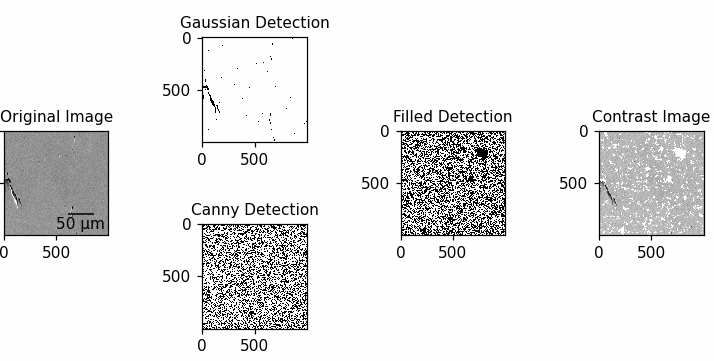

Local Gaussian thresholding is applied over a pixel distance referred to as Gaussian range, which is optimized for the observed defect dimensions. The Gaussian fidelity parameter is adjusted to control the sensitivity of thresholding, determining local threshold values as a function of brightness distributions within the Gaussian curve.

Then Canny edge detection is applied to outline defect boundaries, with the process controlled by three key parameters. The Canny Ksize defines the length of the square kernel used for the inherent blurring process, optimized according to defect size. The Canny sigma value regulates the strength of the blurring, affecting edge smoothness and noise reduction. Finally, the Canny thresholds set the brightness limits for boundary identification, defined by a minimum and maximum value to ensure accurate edge detection.

To eliminate noise and improve defect contours, morphological operations are applied, including one dilation and one erosion step using an elliptical kernel with a radius of five pixels.

Parameter Optimization¶

As dwell time decreases, noise levels increase, necessitating parameter adjustments to maintain detection accuracy. Two complementary tools assist in this process. The first is an interactive slider tool that enables real-time adjustment of Gaussian fidelity and Canny thresholds. It provides a preview over a small area of the micrograph, allowing the visualization of parameter effects and facilitating precise optimization. The effects of adjusting these parameters on the detection process are visualized in Figure 2.2. Alternatively, the second tool employs Bayesian optimization, where input points for each class - defects and background - are labeled. Using this input, the algorithm iteratively determines the optimal parameter values, achieving accurate detection results with minimal manual adjustments.

Defect Analysis and Metrics¶

The algorithm quantifies and filters the detected defects based on the following metrics:

- Location of defect and centroid position

- Size (area)

All defects are characterized by their specific corresponding area, expressed as numbers of pixels, which can be converted into area in μm². - Roundness

Calculated as , with corresponding to the area (as previously determined), and being the perimeter calculated by summing the number of boundary pixels of the defect. - Orientation

Two main types of defects are of interest in the model system of a metal AM sample: cracks, which may include multi-path structures, and pores, characterized by high roundness.

Similar to Ellendt et al., 2021, roundness is used as a morphological criterion to distinguish between these two categories, with each requiring a different method for orientation determination.

For defects with a roundness greater than 0.3 — classified as pores — an ellipse-fitting approach, implemented using the Scientific Python package Walt et al., 2014, calculates the major axis angle.

In contrast, defects with a roundness below 0.3 — classified as cracks — are analyzed using a skeletonizing method Walt et al., 2014 that identifies the longest straight boundary line to determine orientation.

Orientation is defined as the angle of the defect’s major axis relative to the horizontal.

Defects with a roundness exceeding 0.7 are excluded from orientation analysis, as their high roundness precludes a specific orientation.

Defect data, including location, size, roundness, and orientation, is saved for further analysis. This is done using Feather files, in which each defect is added as a new entry, including all the information on the metrics above and all the pixel coordinates that constitute the defect.

Output and Visualization¶

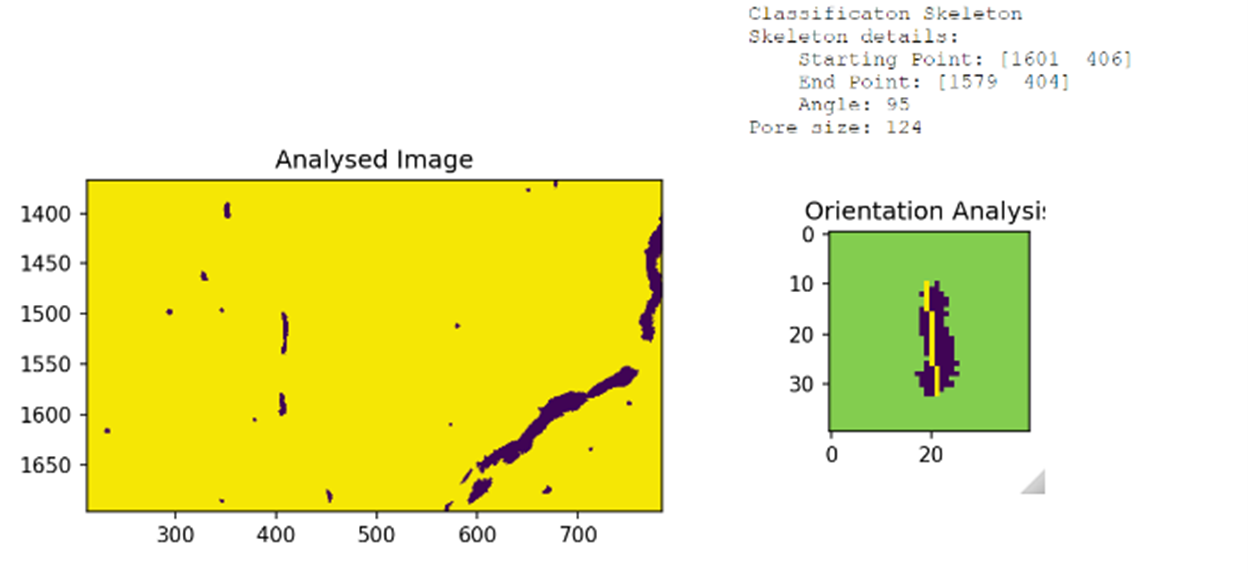

Figure 2.3 presents the results of defect classification and orientation analysis. The binary classification of defects is shown on the left, highlighting identified pores and cracks, while the orientation analysis on the right provides insight into the angle and structure of these defects. Other statistical representations of the data can be selected through the drop-down menu.

The details presented in Figure 2.3 serve as one example of the algorithm’s output, they further include a range of visualization tools implemented to comprehensively evaluate and interpret defect characteristics, as outlined below:

- Binary maps

Highlighting detected defects for comparison against raw images - Bubble plots

Showing defect size distributions with frequency metrics - Rose diagrams

Illustrating defect orientation dispersion relative to the reference axis - Bar charts

Numbers of different defects categorized by their descriptors – implemented here pores and cracks - Scatter plots

Defect area vs distance from a given reference point

Assessment of defect detection¶

Detecting defects reliably depends on the interplay between algorithm optimization and image acquisition parameters. The Bayesian optimization approach for determining the algorithm parameters, initialized with 20 input points, provides a strong starting point for selecting optimal detection parameters tailored to specific datasets. However, manual fine-tuning is often necessary to ensure reliable detection across the analyzed area. Table SI.1 and Table SI.2 in the supplementray materials outlines the detection parameters used to achieve the presented results.

When comparing detection accuracy across multiple image acquisitions, achieving an exact pixel-scale match would be ideal. However, this is not feasible due to practical limitations of the intrinsic scanning mode in SEM imaging. For each combination of dwell time and pixel size, the entire area is scanned in a stop-and-go motion, where only after one set is completed does the stage return to the starting point to acquire tiles with new settings. Inaccuracies in the SEM stage movements during acquisition can lead to misalignments, making a direct pixel-based comparison unfeasible.

To address this, we developed two key metrics: Area Adjusted Agreement (AAA) and Error. These metrics are designed to quantify the retention of defect information and accuracy as dwell time decreases. Using only two metrics, we capture the evolution of defect detection with reduced dwell time.

Defects are matched between the benchmark dataset — acquired with a pixel size of 195 nm and 10 µs dwell time — and all subsequent datasets. This benchmark was chosen as it offers the best combination of pixel size and dwell time, despite containing some inherent uncertainty. To account for small misalignments, a defect in the datasets analyzed is considered a match with the benchmark if the following criteria are met:

- The Euclidean distance between their centroid points is less than 40 µm

- Their area differs by less than 50%

- Each defect in the benchmark is matched only once by minimizing the area difference between the test defect and the benchmark defect

Additionally, to further reduce noise effects and ensure that detected features represent actual defects, only defects with a size of at least 5 pixels are considered.

In some cases, a "filtering constraint’ is applied, defined as the product of the number of pixels per defect and their roundness. This helps eliminate noise and artifacts, as these are often characterized by small sizes combined with irregular shapes (low roundness). The corresponding values are indicated in the results whenever this filtering is applied.

AAA sums the total area of correctly detected defects in the inspected image and divides it by the total defect area in the benchmark, reflecting the proportion of defect area retained as dwell time decreases. However, AAA values exceeding 100% can be explained by the edge effects in SE images, caused by the ETD’s sensitivity to topographical variations. These effects enhance signal intensity, producing brightness distortions that obscure defect boundaries and inflate measured areas by 10–20%. This introduces inconsistencies in defect sizing, even when other characteristics, such as roundness, are accurately detected. When large defects — already accounting for most of the total defect area — are affected, their oversized measurements still match the benchmark, artificially inflating the value of AAA.

Since the total detected defect area varies with dwell time, the value of AAA alone does not indicate defect detection accuracy at lower dwell times. The Error metric is introduced to address this, quantifying the proportion of incorrectly detected defect areas relative to the total defect area in the lower dwell time image. Together, values for AAA and Error provide complementary measures of detection accuracy. Over-detection can lead to an AAA of 100% while still yielding a non-zero Error value. Conversely, if only a subset of benchmark defects is detected at a lower dwell time but without introducing false positives, AAA may fall below 100% while the Error remains zero.

- Bradski, G. (2000). The OpenCV Library. Dr. Dobb’s Journal of Software Tools.

- Lobato, I., Friedrich, T., & Aert, S. V. (2024). Deep convolutional neural networks to restore single-shot electron microscopy images. Npj Computational Materials, 10(1). 10.1038/s41524-023-01188-0

- Cormen, T. H., Leiserson, C. E., Rivest, R. L., & Stein, C. (2009). Introduction to algorithms (p. XIX, 1292 S. (unknown)). MIT Press.

- Reimer, L. (1998). Scanning Electron Microscopy - Physics of image formation and microanalysis. Springer Series in optical sciences.

- Ellendt, N., Fabricius, F., & Toenjes, A. (2021). PoreAnalyzer—An Open-Source Framework for the Analysis and Classification of Defects in Additive Manufacturing. Applied Sciences, 11, 6086. 10.3390/app11136086

- van der Walt, S., Schönberger, J. L., Nunez-Iglesias, J., Boulogne, F., Warner, J. D., Yager, N., Gouillart, E., Yu, T., & the scikit-image contributors. (2014). scikit-image: image processing in Python. PeerJ, 2, e453. 10.7717/peerj.453